Case 4 - 25 year old with pain after playing basketball.

Tuesday, August 21, 2018

Case 3

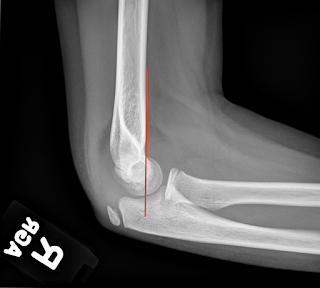

The pediatric elbow - most non-pediatric radiologists strongly dislike the pediatric elbow as there are many things going on. In elbows, adult and pediatric alike, looking at the alignment and for elevated fat pads is always the first step. In this case, you can see that both of the fat pads are elevated, which indicates an underlying effusion from hemarthrosis. So, in the setting of trauma, we at LEAST know there is an occult fracture present.

In adults, this most commonly indicates a radial head fracture, but in children, it is most commonly a supracondylar fracture. At this point, looking at the alignment allows you to evaluate for a supracondylar fracture using the anterior humeral line. The anterior humeral line should cross through the middle third of the capitellum. In this case, you can see that the anterior humeral line is normal.

In pediatric elbows, evaluating the ossification centers using the mnemonic, CRITOE is important. This mnemonic stands for the order of formation/appearance of the ossification centers in the elbow and the approximate age at which they appear (ages 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11).

For more reading, here's a good resource/review:

Pediatric Elbow

The pediatric elbow - most non-pediatric radiologists strongly dislike the pediatric elbow as there are many things going on. In elbows, adult and pediatric alike, looking at the alignment and for elevated fat pads is always the first step. In this case, you can see that both of the fat pads are elevated, which indicates an underlying effusion from hemarthrosis. So, in the setting of trauma, we at LEAST know there is an occult fracture present.

|

| Positive Sail Sign - Hemarthrosis |

In adults, this most commonly indicates a radial head fracture, but in children, it is most commonly a supracondylar fracture. At this point, looking at the alignment allows you to evaluate for a supracondylar fracture using the anterior humeral line. The anterior humeral line should cross through the middle third of the capitellum. In this case, you can see that the anterior humeral line is normal.

In pediatric elbows, evaluating the ossification centers using the mnemonic, CRITOE is important. This mnemonic stands for the order of formation/appearance of the ossification centers in the elbow and the approximate age at which they appear (ages 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11).

Capitellum - age 1

Radial head - age 3

Internal (Medial) epicondyle - age 5

Trochlea - age 7

Olecranon - age 9

External (Lateral) epicondyle - age 11

In our case, we have a 9 year old, so we should have all of the ossification centers present, except the lateral epicondyle, and they should be normally positioned. Our patient has all present (including the external/lateral epicondyle) and all are normally positioned. Sometimes, after all that work, pediatric elbows are not fulfilling because you can't always find the fracture. At this point, I would dictate this case as positive for elbow joint effusion, consistent with occult fracture.

Here is a good example of a supracondylar fracture:

|

| AHL - through the anterior third of the capitellum |

Pediatric Elbow

Monday, August 13, 2018

Case 2 Answer:

This is a case of perforated appendicitis. The hyperdense structures on the images are appendicoliths; of which, this little guy had two. Remember to always look for the appendix on every case even though it's not a standard field in our templates. This serves two purposes - one, it's good for the patient. Secondly, it helps you get better at finding the appendix. I start with the axial images and, if I can't find it, I find the coronal to be very helpful in locating it. If I can't find it on soft tissue windows, using the lung windows will often help the appendix stand out.

This little guy had a frank perforation, which can be seen as mucosal discontinuity on the coronal images. You can also see a periappendiceal abscess (arrow on the axial; star on the coronal images). The last image was not present on the original case. However, I included it because it shows a second abscess, distant from the appendix, in the upper abdomen with reactive jejunitis of the proximal jejunum.

This is a case of perforated appendicitis. The hyperdense structures on the images are appendicoliths; of which, this little guy had two. Remember to always look for the appendix on every case even though it's not a standard field in our templates. This serves two purposes - one, it's good for the patient. Secondly, it helps you get better at finding the appendix. I start with the axial images and, if I can't find it, I find the coronal to be very helpful in locating it. If I can't find it on soft tissue windows, using the lung windows will often help the appendix stand out.

This little guy had a frank perforation, which can be seen as mucosal discontinuity on the coronal images. You can also see a periappendiceal abscess (arrow on the axial; star on the coronal images). The last image was not present on the original case. However, I included it because it shows a second abscess, distant from the appendix, in the upper abdomen with reactive jejunitis of the proximal jejunum.

|

| Periappendiceal abscess |

|

| Rounded mucosal layer is enhancing with an intraluminal appendicolith |

|

| Blunt ending, tubular structure, which is the appendix. You can see the mucosal discontinuity with adjacent fluid collection/abscess. |

|

| Star - abscess |

|

| Second abscess in the epigastric region. The arrow is demonstrating reactive wall thickening of the proximal jejunum (a reactive jejunitis) |

Sunday, August 5, 2018

Case 1 Answer

Being and ER and Trauma radiologist by trade, I had to start with a trauma case. While we do not see a lot of higher-end trauma here, we still do see some and it’s always nice to review these cases as trauma is the leading cause of death in the US for patients under the age of 45. Conveniently, the spleen is the most commonly injured organ in blunt abdominal trauma, hence why I picked a splenic laceration as the first case.

This case demonstrates a grade III splenic laceration as the laceration was just over 3 cm in length. There are two flavors of injury to the spleen, either a laceration or subcapsular hematoma. A laceration will be an irregular, hypoattenuating linear structure in the splenic parenchyma, just like this:

This case demonstrates a grade III splenic laceration as the laceration was just over 3 cm in length. There are two flavors of injury to the spleen, either a laceration or subcapsular hematoma. A laceration will be an irregular, hypoattenuating linear structure in the splenic parenchyma, just like this:

Conversely, a subcapsular hematoma will be low-density, curvilinear fluid surrounding the splenic parenchyma, which is contained by the splenic capsule. You can have one, the other, or both. Evaluating the fluid for an irregular, blush of hyperdense contrast material is of utmost importance for both of these injuries, as that tells the ER physician/Trauma surgeon that there is active bleeding and they may need to call IR or take the patient to surgery. In this case, we did not have active bleeding. I'll have a case with active extravasation later in the year.

The American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST) has a grading scale for traumatic injuries and, generally, a grade 2 or lower injury will be managed conservatively. A grade 3 or higher injury will oftentimes require surgical management. I try to always put in the relevant grading scales as it drives management. Don't try to memorize them; thankfully, these grading scales are online:

The American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST) has a grading scale for traumatic injuries and, generally, a grade 2 or lower injury will be managed conservatively. A grade 3 or higher injury will oftentimes require surgical management. I try to always put in the relevant grading scales as it drives management. Don't try to memorize them; thankfully, these grading scales are online:

Additionally, here’s a great radiology article to get you started on MDCT of Blunt Abdominal Trauma.

Next Case is up.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)